In episode 11, I’m joined by a visitor from Peru: ecologist and field researcher Chris Ketola. With 25 years’ experience working with wild animals, I’m intrigued to know how time in Equatorial Africa compares with his life in the Amazon.

During a ten-week tour of Uganda, Ketola and Fauna Forever co-founder Chris Kirkby led a team of 14 volunteers. Together they covered 3000 km, capturing (and releasing) 2000 birds and bats at eight sites across the country.

Listen to my conversation with Chris Ketola, accompanied by a backdrop of birdsong, as he reveals:

- What are his tips for organising a trip to Uganda?

- What did the baboons do to his mosquito net?

- Which are his favourite Ugandan foods?

- How does he reassure people not to be afraid of snakes?

- And, why does he find bats so adorable?

Join me – Charlotte Beauvoisin, author of Diary of a Muzungu – on the shores of Lake Victoria as I compare notes with Chris Ketola.

Scroll down for the full transcript of this week’s episode.

Welcome to my world!

Tune in every week to The East Africa Travel Podcast for the dawn chorus, travel advice, chats with award-winning conservationists, safari guides, birders, lodge owners, and wacky guidebook writers.

- Sign up to my newsletter to receive an alert for new episodes.

- Subscribe to the East Africa Travel Podcast on Apple, Spotify and all the popular podcast directories.

- Follow Charlotte Beauvoisin, Diary of a Muzungu on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

- If you have any questions or comments, I’d love to hear from you.

- Send an email or a Whatsapp voice note.

Stay tuned for more sounds from the jungle!

Episode 11. From the Amazon to the Equator. In conversation with Chris Ketola

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Hello, welcome to The East Africa Travel Podcast with me, Charlotte Beauvoisin, author of Diary of a Muzungu. You’re listening to episode 11.

Canadian Chris Ketola is fascinated by creatures that most people consciously avoid: bats and snakes. His title is, wait for it, Terrestrial Vertebrae Ecologist and Head Field Research Coordinator for the NGO Fauna Forever in Peru, and he recently visited Uganda for the first time. When someone has spent 25 years studying wildlife, in zoos, animal rescue centres, and seven years deep in the Amazon, and has specialised in tropical wildlife much of that time, you might ask yourself what there is left in the world for him to see? But Uganda did not disappoint.

I was therefore really intrigued to find out what he did in Uganda and what he really took away. Unlike the average tourist, Chris was here in Uganda for a whopping 10 weeks and traveled all around the country.

Chris and I chatted at Casa Turaco in Garuga on Lake Victoria, the home of Dr. Roger Kirkby, who very sadly passed away as we were preparing to launch this podcast.

Roger was a committed environmentalist, and a firm friend of Sunbird Hill. He had stayed with us and he brought friends, and I know that he’d have really loved the podcast. and everything that I’m trying to do, so this episode of the podcast, episode 11, is dedicated to Roger and to Chris, his son, who is one of the co founders of Fauna Forever, and to Asha, Roger’s daughter.

Thanks for listening.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Chris Ketola, thank you very much for accepting my welcome to be on my podcast.

I’m very excited to be talking to you because I know you’ve had one hell of a trip here. You’ve been in Uganda for how many weeks now?

Chris Ketola: I guess about 10 weeks since the middle of January.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And I remember when we first met, I was asking you how different Uganda is to the Amazon, and I remember you saying that the weather here is just a lot easier. How would you describe it after traveling so widely now?

Chris Ketola: I would still say it’s much easier, you know, it’s quite variable. It’s not quite the extremes that we get in Peru with the cold winter nights in the high Andes, although I didn’t go to the Rwenzori (Mountains). I know it is up there cold, but it definitely has some variation: the forested areas over in Kibale Forest are definitely cooler there at night. And even some of the Savannah areas at night can get quite cool. And then, obviously the daytime and in the sun in the Savannah it’s very hot. There’s no question. Overall it’s a much more manageable temperature and the humidity, it’s so much lower.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: You are here in the rainy season. It’s a very hot day today. We may have thunder tonight. Have you enjoyed this variation in the weather that we have?

Chris Ketola: For me, as you know, as an ecologist, I like seeing the seasonal change and to be honest, I would love to be here another month or two and just see how it changes. Especially in Savannah. I’ve asked some of the people we work with to send me some photos of what it’s like just so I can see the change because it’s so dramatic. I’d love to see that.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And so just rewinding back a bit, you have a really fantastic title. You are a terrestrial vertebrate ecologist and a head field research coordinator in the Amazon – and the organization’s Fauna Forever, is that right?

Chris Ketola: Yeah, that’s correct. Titles are, you know, it’s like a human construct. We all need to give ourselves a title. Essentially what that means is I have experience and expertise working with, researching and studying, basically anything that lives outside of the water that’s got a backbone. So that would be birds, bats and other mammals, it would be reptiles, it’d be amphibians. I don’t consider myself a botany expert. I don’t consider myself a fish expert and not an invertebrate expert. Reptiles and amphibians in particular would be my areas of expertise.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: I know you particularly love snakes because I’ve seen you a few places with these gorgeous – but to some people – very scary-looking snakes. But how did you get into snakes?

Chris Ketola: My whole background’s probably a whole podcast of its own, but essentially I was fortunate enough from a very, very young age, pretty much when I was born, to grow up around, more, unique animals. I guess some people use the term exotic, but non domesticated animals we’ll say. And that definitely involved working with a lot of animals, including snakes and reptiles, and in my teens even being around and helping care for venomous reptiles, venomous snakes, cobras, for example, gaboon vipers in captivity.

I’ve done some field work with reptiles and then amphibians in Canada, but then the majority of my fieldwork experience with reptiles, amphibians has definitely been in the Amazon, in Peru. And in terms of snakes particularly, I find them to be obviously fascinating animals, I mean: they’re very beautiful, they’re very interesting and I often find that some of the ones that people are most fearful of are often some of the sweetest and calmest ones. Of course, it can be dangerous if you’re not careful, but their actual personalities are often quite calm and quite nice if you know how to handle them properly.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: In Uganda, you must have come across this everywhere you’ve worked, people are terrified of snakes and there seems to be this feeling that you kill it first, and ask questions later. So how’d you deal with that when you’re with local people who’ve been brought up to fear them?

Chris Ketola: Yeah, it’s a good question, because you’re totally right, it’s certainly not unique to Uganda or Africa. Everywhere in the world. I mean, tropical regions in particular, but even the United States and even in Europe; anywhere in the world, people naturally are seen to be afraid of snakes. And it’s understandable that we would be fearful of something that in our evolutionary past could have been very dangerous to us, you know. Just because I don’t have fear of them in the way that someone else does, it doesn’t mean that everyone should feel the way I do.

But I think the important thing to get across is that if you’re scared of something, you don’t have to kill it. If you want to be scared of it, that’s your choice and I respect that. It may not always be founded, but at least I respect the fear. But why do you kill something that you’re scared of when it’s really not a risk to you directly?

That’s the big thing. If we just use our brain and our logic in our actions, we can realize to give them space, snakes never chase or attack you. They will only defend themselves. If given space, snakes will never bite you. That’s a very important thing for everyone in the world to understand. The risk of snakes is extremely low, but a lot of the issues that occur is because people are not responsible and not smart in how they move and interact with their environment. And these few accidents that are human caused, lead everyone to assume that snakes are evil and we must kill them.

That snake is not evil. It’s living its life, so we just have to learn to live with it. We share the planet with them. We don’t dominate the planet, you know? So that’s what I would try to get across people is accept that you have fear. That’s okay, but how do you respond to the fear? It should be changing your behavior and learning to live with that animal.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So you’ve been here doing a number of things: education (you were just referring to active conservation research), but you came with volunteers. And those are people that are on some kind of holiday as well as a work experience. You’ve touched on many things, I think in two months, haven’t you?

I was listening to something on Instagram today that you recorded: you’ve covered 3000 kilometers and over a thousand species of birds.

Chris Ketola: In terms of the number of species that we saw and either recorded like visually or acoustically or physically captured in our ringing, our mist nets, were around 400 species of birds, and then for bats, we ended up at 43 species. In total it was 662 bats. For the birds, we’re still putting that data in, but it’s around 1200 to 1400, so nearly 2000 specimens captured as well, and of course captured and released. They’re fine.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So they’ve all been released now?

Chris Ketola: Oh, yeah. They’re all released quickly the same morning or the same night after we catch them. But it’s a lot of data that we have on many, many species from, as you alluded to, eight different research sites, covering most of the country and most corners: the northwest, the southwest, Eastern, many different regions around here, Lake Victoria.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So you started off in Lake Victoria. You’ve been to Lake Mburo National Park, Queen Elizabeth; you’ve been to Murchison Falls National Park. You’ve been to Pian Upe wildlife Reserve, and lots of places in between.

Chris Ketola: Yeah. And the other park, we work near, of course, was Kibale NP with Sunbird Hill.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Oh yes, of course!

Chris Ketola: So this particular trip, we didn’t work within parks or reserves, we chose to work in sort of private conservation areas on the edge of these parks and reserves.

The wildlife there is an interesting mixture because these are not protected by the government in that classic reserve or park way, but they’re often protected by private individuals or private organizations.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So we are talking today at Casa Turaco, which is in Garuga. It’s on the peninsula on Lake Victoria. And we can almost see the airport, can’t we? Across the bay is Entebbe International Airport. This was the first place you came to; you came with Dr. Chris Kirkby, who is a co-founder of Fauna Forever. You spent a few days here, I think, didn’t you, acclimatizing?

Chris Ketola: We actually spent the first week here. And even here, got some very interesting bats, some very interesting birds. Surprising diversity in the quantity of species here.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And this is just private land, isn’t it? It’s not protected. It’s not a sanctuary.

Chris Ketola: No. It’s just protected by the owner, Dr Roger Kirkby so it’s very interesting, how even a small little private piece of property can be a home to so much diversity.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: You keep mentioning bats, I think you’re quite into bats, is that right? What is it about them that appeals to you?

Chris Ketola: There’s so many things. One of the things I love about birds and bats that they share in common is, of course they fly. It’s the fact that when you have animals that fly, they often have an incredible suite of adaptations to allow them to fly.

There’s just a lot of aspects of their biology and ecology that are fascinating. And then finally, I’m not going to lie, they’re just really cute. That matters too. And I understand some people, some listeners might think they’re kind of creepy, and again, I respect that.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: It’s another (group of) maligned species, isn’t it?

Chris Ketola: It is. But I think that when you see them up close, and you understand what they do and how they do it, they are really fascinating; I would struggle for anyone to really think they’re not cute when they see the little face twitching and looking at you. That’s really adorable.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: We’ll have to make sure that we share some photographs in the show notes so people can see exactly what you’re talking about. I have seen some of your great photographs of bats taken at Sunbird Hill. Podcast listeners will know that I live on the edge of Kibale Forest in Western Uganda, that’s famous in many people’s eyes for the chimps and the birds. But yes, you’re bringing a new perspective to it. You’ve really helped us put bats on the map. I think you’ve been teaching people as well up there, haven’t you, how to identify bats or monitor them?

Chris Ketola: Yeah, I mean, obviously when it comes to working with bats, it’s quite specialized. It does require a certain set of skills and knowledge and also certain vaccinations and handling skills. They’re not as dangerous as people would think, but there is a certain danger involved, you know, if they bite you and that kind of thing.

During our time up at Sunbird Hill, we obviously worked with the team there a lot. Their primary interest is definitely birds. They love birds and they’re amazing with birds and also snakes reptiles and amphibians, but I think they really enjoy learning more about bats and understanding more about how important they are, how much diversity there is.

One of the most rewarding nights we had with bats, we actually went and sampled some bats in Bigodi Swamp, which is managed by KAFRED as an organization, you know very well. And it was really nice. We went there with the Sunbird Hill team and our volunteers and the nets and we just set them up. The people in the area, the community just naturally just came, and, we had at some points, 10 to 30 people clustered around our table, asking questions and learning about bats and, they weren’t all against them or scared of them. And what I was really taken by was that the questions we were getting in many cases were actually very complicated.

A lot of people, it doesn’t matter where you’re in the world, have a tendency to ask some very basic questions about bats because they’re so misunderstood. What type of fruit do they eat exactly? How do they pollinate? How do they spread seeds? How do they catch an insect if they’re doing that? What type of insect? It was just great to have the general reception from that community to be: “Bats are cool. This is great!” Not “Oh, they’re gross! Why are you doing it?” Which is what we get so often in the general public.

I found it super, especially as some of your listeners would definitely know with the history across the world and specifically Africa and very specifically Uganda with bats and some of the diseases that have occurred either because of bats or sometimes not because of bats, but the blame has been put on them, which is often the case. It’s still refreshing to see people not having an ingrained fear, which I almost would’ve expected.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: That’s really good to hear that about KAFRED. So there is a swamp walk, Magombe Swamp Walk. KAFRED was set up in the end of the 1990s and it’s a tourism activity and a sanctuary, but it’s also a training ground for so many of the young people that you’ve met at Sunbird Hill and other places in the region.

It’s great to hear how deep that curiosity is.

Chris, in terms of tourism, I’d really love to know what some of the favorite things are. Let’s start with wildlife. You sent me this fantastic photograph of a leopard, an absolutely gorgeous photograph. And so where did you find that? How did you find that?

Chris Ketola: So the leopard, yeah, that was quite a morning!

As part of our programme for our volunteers, the majority of their days are very hard work, but we wanted them to have the opportunity if they were with us for one or two months to, you know, experience more of the typical Africa you’d see on TV or a program, and that meant doing a safari game drive. So, we decided to take them to Murchison Falls National Park and also to, Queen Elizabeth.

The leopard in particular was on our second safari in this trip. We started out in the morning and right away, like almost immediately, we found a female and a male lion with three cubs, and that was very right away: boom! There you go. Playing cubs with the mum; the male roaring, amazing. And then we continued for a while.

And then our driver, Francis got a phone call from someone and he’s just started driving fast. “Francis, what happened?” He’s like “there’s a cat.”

And I said to him, “is it a leopard?” And in my mind it’s like, “it’s not a leopard.”

“Yeah, it’s a leopard.” I’m like: no!

Chris Ketola: And we took this corner and that corner, and we came up to: one car was there, a beautiful leopard laid out, sleeping on a log. Perfect visibility. Not obscured. Amazing views for an hour.

And then on the way out, we saw a young Martial Eagle eating on the ground. We saw two Bateleurs. Everything went perfect for that safari. We were pretty high on that. I think lions are something I expected we’d see; elephants, you know, but, the leopard I knew wasn’t a guarantee, especially a view like that, so I was very happy. It was one of the collared leopards for the carnivore tracking program, but we kind of found it, I guess you’d say naturally. We didn’t track it, we just found it. It was exciting to see it and a great surprise.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: I once saw a leopard in Queen Elizabeth when I was on the Kazinga Channel boat ride. Did you do the boat ride?

Chris Ketola: Yes, we did. It was very interesting. I mean, so many hippos. It was really, really good for birds. And then at the very end of it, we actually had a nice little finishing touch with a really nice family of elephants. Really close. It was also interesting to see the fishing communities on there and how they sort of interact and live.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: People do get attacked by hippos and they do get eaten by crocodiles, so, yeah human wildlife conflict is alive and living, especially in Queen. I used to work on the edge of Queen Elizabeth. We were excavating elephant trenches, and looking at interactions to try and stop the elephant’s crop raiding and so on.

It’s a very interesting part of the world, Queen Elizabeth, and you stayed in Mweya. How did you find it, living in the middle of the park on that peninsula?

Chris Ketola: I found it really good. It was really nice to wake up and have, you know, warthogs. So it was very natural, very wild. I mean, there was elephant dung right behind where we were sleeping.

The accommodations were: they are what they are. They’re not luxury, but they’re very suitable. So, you know, if someone’s looking for a basic bed that’s clean with a shower – it’s that. If they want luxury, well, they can go to the lodge just up the road.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So you were in the Uganda Wildlife Authority guesthouse, weren’t you? And then some of you pitched your tents?

Chris Ketola: We actually ended up using the cottages fully. They had enough space and they were happy to let us take it. And then we ended up having, as you suggested, all of our meals at the canteen. The food was really good and it was very efficient. And the food, the pricing was absolutely standard pricing, not expensive for me at all. Nothing high at all. 30,000 UGX each plate. Very good portions.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So that’s less than, that’s like $8 or something like that.

Chris Ketola: It was great. Honestly. Open whenever you wanted it. I mean, for someone on a budget who wants to have a really “in the park” sleeping experience, I couldn’t recommend it more really. I’m very happy with that suggestion and, thank you personally. It was great.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Lovely. I’m so pleased it worked out for you. I like Tembo Canteen. It’s part of the Uganda Wildlife Authority compound, in the middle of the park and you can sit there having your tilapia and chips and look over the channel and, watch the elephants and the birds and spoonbill, one of my favourite birds .

Chris Ketola: It was really nice to just be in the park for what was essentially three nights fully, and just be immersed, so that aspect of it was great. Those cabins have many bats living them so that was fine for us. I think for some people it might be a bit of an adjustment, but for us we loved it.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Absolutely. You must have been in your element!

So what were you doing up in Pian Upe – more research?

Chris Ketola: We were working again just outside of the reserve with a new NGO the Kara-Tunga Foundation and they have a number of properties they manage now and they’re starting to work with, but ours in particular was just on the north side of Pian Upe, right near Mount Kadam. We were the first guests to ever stay there, which was very exciting and very kind of honored about that.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: So this is in Northeast Uganda. It’s an area of the country that’s very undeveloped for everything, not only tourism. It’s interesting that you’re part of that cycle at the very early stage.

Chris Ketola: To give more context: you’ve got the big mountain range there and east of there is Kenya. It’s kind of that dividing mountains between Kenya and Uganda. It’s very different habitat there too. I mean it’s Savannah, but it is a drier Savannah that’s a lot more like Serengeti (Tanzania), a lot more like some of the classic traditional habitat you often see on TV. The bird life there was definitely different.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: What did you see? Make me jealous!

Chris Ketola: 110 species of birds. For me, a really big highlight was seeing a Lanner Falcon hunting. Lanners for me are a very, very special bird.

We actually caught a Narina Trogon, which was amazing. It was very diverse for an area that on the surface wouldn’t seem to be. As you go up the foothills, you start to get little patches of forest that are nestled in the foothills, in the valleys.

Getting a Narina Trogon in that area and getting, for example, blue spotted wood dove and emerald spotted wood dove; they normally are not found in the same area at all: one is Savannah dry and one is more wooded area, and even though it’s so close (2 km walk or less) you really get a different community of birds and bats as well. It was very cool. It was one of the best sites we were at, in my opinion.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Fantastic. So I wanted to ask you about the Shoebill. I know it’s one of the top attractions in Uganda. And for you, so you finally saw it! But only briefly – and I think you got rather wet!

Chris Ketola: When we finished our work, the team was together back here in Entebbe. We ended up deciding to go and try at Mabamba Swamp for it. Yeah, the weather wasn’t great.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: We’ve had a lot of heavy rain.

Chris Ketola: We decided, you know: “we’re tough!” We got in the boat and went out around 11am, when the rain let up. The search was great. We had a lot of fun and we ended up seeing it and we actually saw it for a good 45 minutes. We got really good views.

We got pretty wet, but we’re happy we saw it. The Shoebill is a pretty mythical bird. Pretty, pretty unique bird. I mean, it’s the only one in its family in the world. And you’re right, for a lot of people, it’s one of the avian highlights of the country and of Africa arguably so, it was very nice to see it.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: We only have a few hundred pairs, I think, or 300 individuals rather in Uganda, and to have one with an immature is very unusual, isn’t it?

Chris Ketola: Yeah. I mean, speaking to the guide who took us, who is very knowledgeable and knows the swamp well, he said that there’s two young from this past year, so that’s really good.

It’s a species that is vulnerable globally and it only has probably around 10,000 birds in the world left. And they’re naturally rare, because they have very specific habitat requirements; of course, with a lot of those habitats being drained or polluted or burned or whatever, it just naturally cuts it down. We still have a lot to learn about what’s really happening with them across their range in Africa.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And we both know Nkima Forest Lodge, which is very close to Mabamba Bay, and I was talking to the owner, Elaine recently, and she said, local people really love the Shoebill because there are jobs connected with it and it’s bringing in money, it’s bringing visitors. And she said it’s so great to see how people really treasure and want to preserve the bird. It’s really good to see local communities loving and protecting what they have.

Chris Ketola: You know, when you can put a value on something, over and above just what it looks like, some people can often, they can understand it and appreciate it even more. I guess that’s the power of ecotourism, right? It can have a very positive impact on conservation when it’s executed properly, without a doubt.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And beyond ecotourism and conservation. I wanted to ask you some other impressions of Uganda. How do you find the food? Do you have any things that you really enjoyed trying?

Chris Ketola: Uganda’s food is better than most of South America.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: What makes it better?

Chris Ketola: Oh, it’s got flavor! It’s got flavor. It’s got spice. Beans here actually taste like something. The food is quite good. I was very impressed. We didn’t eat luxury. We didn’t eat what I would call tourist food. We specifically told all the cooks and all the people we worked with: give us posho, give us matooke, give us beans, give us rice. What I really did enjoy that I haven’t really had before is chapati. It’s just amazing; them and rolexes. I know it’s a basic thing, but man, we are addicted to that!

Charlotte Beauvoisin: But I think if you’re, a field person and you’re eating on the go, I think that works really well, doesn’t it? To have a rolex, which is an omelet wrapped up in a chapati.

Chris Ketola: And just chapati and beans. It’s just so good. I mean, I guess if I’m being blunt, there was nothing in Uganda that was like “world class, I’d travel the whole world to come and have it” but to me what matters more is what do you eat regularly? Not “what is the best dish you ever had?”

What I care about is that most days I was happy and excited to eat, whereas I don’t always say that in Peru, so actually I really enjoyed the food here.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: What about the drinks? Have you tried any local drinks?

Chris Ketola: Yeah, most of the beer I’ve had here has been really good. The Nile and the Club, I mean, they’re cheap, they’re basic, but they’re good. The Banange, I think it is?

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Oh, Banange beer. Yeah, craft beer.

Chris Ketola: That’s really good. When you have a group the size we had, and you’re here for two / three months, you have to think of the cost, but my God, if I was here for a week or two – it’s so cheap to eat here!

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And we have huge avocados, don’t we? Famously sweet pineapples.

Chris Ketola: Bananas. Bananas everywhere, but very tasty bananas. No complaints about the food at all.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: That’s great to hear. And then now, what about travel tips? I know you’ve traveled a lot, you’ve lived for many years in Peru in the middle of the rainforest, although you are originally from Canada, but did you come here and find there’s something that you hadn’t thought about? When you come back next time, what would you do differently?

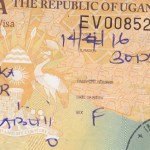

Chris Ketola: I guess three things that I would think of is: number one. It is quite expensive traveling here. Our volunteers really had no major problems. They all came from various airlines and it was all quite smooth. The immigration aspect – even extending the visa – was reasonably straightforward. But honestly, all of that was very smooth but in terms of, in the country, when you choose to travel somewhere, the actual hiring of a car or a bus was more expensive than I’m accustomed to in Peru. I think we under budgeted that way and we have to learn from that. It’s okay. We learned, it’s not cheap, no criticism, it’s just something to be aware of.

I would also say that, if someone’s listening and planning their trip, don’t Google it and expect that to be what it’s going to be, because Google doesn’t realize the quality of the roads. It will take you the most direct route, and then when you talk to the driver, the driver tells you that road is either not passable or it’s potholes, or will go so slow that it’s faster to go this route, so many trips we took that said they were six hours, were nine or ten…

Charlotte Beauvoisin: According to Google Maps? Right. I see.

Chris Ketola: So really budget for that. We got to the point where whatever Google said, we usually added at least 30% time to that minimum and you can imagine for anybody listening: if they’re expecting to check in at a certain time or planning their activities on that, and they’re right to the minute, leave a big buffer please.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Well, that is why generally speaking, we do recommend people use a tour operator because they know how much time you need to leave to get to A from B, and what might go wrong.

Chris Ketola: The third thing I would say is that if you choose to plan it more on your own (because one of the things I would say about Uganda that’s really interesting is you can, I think, do some planning on your own).

But you’re right, you need someone with experience to help you and having a driver you trust or that is recommended by someone is really important. All of our drivers were good, but there were definitely some that were better than others. If you could either get a tour agency or find a friend or a connection or someone with experience who can help you, that will make your experience much better, let me tell you.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Yeah, definitely. And I do work with a lot of tour operators. In fact, if anybody’s listening and, wants to pick up on some of the tips that Chris has just shared with us, we do have a Travel Directory with various tour operators in there who are all registered, and recommended.

But yes, the guide is arguably the most important person on your trip.

So we talked about some of the birds that you’ve seen and a couple of the bats, the leopard. Any other standout species that you are going to be really shouting about?

Chris Ketola: Yeah, we did track the chimps and that was a very enjoyable experience.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Did you do that in Kibale Forest?

Chris Ketola: No, in Budongo? Budongo, near Murchison.

Yeah, we had a lot of fun with them, and we certainly had no problem finding them.

Two of the highlights were seeing a very large, probably two and a half meter rock python up at the caves, near Queen Elizabeth.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Ah, Maramagambo?

Chris Ketola: Yeah. And we saw that, which was lucky because as soon as it felt a vibration, it actually left, so we only had a few minutes to see it, but it was huge and right there; it was great. Very exciting for me.

And then the other one is: I saw a few forest cobras, but the encounter in Budongo was, quite interesting. When we started the tour, I told the guide, “If you see a snake, let me know because I love snakes and I would love to see it.”

So I let most of the volunteers go ahead and I kind of was at the back. And then after an hour or so, the word came: “Chris go up to the front, there’s a snake”. And of course I knew right away it was a forest cobra. It’s big, it’s black, you could just tell. So I asked the guide: “is it okay if I go closer because I’m very experienced with venomous snakes and I know to be safe. Don’t worry.” We talked and he’s like “you can walk a little closer, I understand you know what you’re doing” so I got a little closer to it.

And this particular cobra had its head over a log. It was a hollow log, it was exploring, so I was able to get quite close safely because its head was hidden and it wasn’t any risk to me. And I was staring at it and taking a photo of it and really enjoying it. (And I will just say for the listeners, don’t do that unless you know snakes).

Charlotte Beauvoisin: “Don’t do this at home!”

Chris Ketola: Yeah, I’ve handled venomous snakes for a long time. I know how to be careful, so no one else should do it. But I felt safe doing it, and the guide trusted me to do it.

But what happened, is after a few minutes I was watching it and I happened to just look up, and about two meters from me were two chimps staring at the same Cobra.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Oh my God. Wow!

Chris Ketola: They did not care I was there because they’re so habituated to people. But they were so focused on the Cobra, to watch it for the group. And then the Cobra decided to pop its head out, and as soon as the head came out of the log, of course the chimps reacted and vocalized and WHOA, WHOA…

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Whoa. How exciting!

Chris Ketola: It was quite a surprise for all of us. And then the chimps left and it was a very cool experience.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: And you are there out of curiosity, but the chimps are there out of fear and guarding the family group.

Earlier on when we were talking, you alluded to another funny story about baboons when you up in Murchison.

Chris Ketola: So we were in Murchison quite a few days, I think 11 days, and we never really had a problem with baboons. We saw them in the area, but they were pretty respectful. And they’re pretty used to people. But I think that they knew our schedule and they knew that normally we were working in the morning, the afternoon, and we were always around our camp.

The second day we did a safari, I think they learned that we were leaving for a long period. They kind of watched us and they’re like, oh, they’re gone so they decided to raid our whole camp and our tents were opened, our bags were opened. They didn’t do too much damage, although they did take one of our nets and they just stretched it around a tree and it was ripped and shredded, so it’s good lesson. You know, we should have been more careful. Don’t underestimate the baboons. They’re smart.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Well thank you so much Chris, for sharing just a few highlights of your incredible 10 weeks and looking forward to finding out more, and following you on Instagram. We’ll share some links in the show notes so people can follow up if they want to know more about your work with Fauna Forever or follow you personally or perhaps be involved in one of your next trips, because you’ll be doing a Uganda trip in 2024, will you?

Chris Ketola: We expect to, yes. We would expect to be here again and we’re still deciding exactly where we’re going to go and how it’s going to work, but, I don’t think this will be the last time we’re in Uganda.

Charlotte Beauvoisin: Hope not. Great. Nice to talk to you.

Chris Ketola: Awesome. Thank you so much, Charlotte. It’s been a pleasure.

Thanks Chris.

If you’ve enjoyed my conversation with Chris Ketola on Instagram, you can look him and Fauna Forever up on Instagram. I’ll put some links in the show notes as well. Chris has a brilliant Instagram feed, beautiful photographs of fantastic creatures, and some great little reels and videos. I particularly liked the outtakes actually.

Not only does Chris have incredible pictures of scary looking snakes and vibrant, huge frogs, you’ll see him getting tangled up in snakes and fording rivers and goodness knows what else, often in the company of researchers and volunteers.

If you like the sound of the trip that Chris organized, you might want to be a volunteer. The team here at Sunbird Hill absolutely loved interacting with Chris Ketola and Chris Kirkby and their group of 14 volunteers. It was a once in a lifetime learning experience for everyone.

If you’ve enjoyed this episode, please drop me a note. Tell me what you think on social media. Perhaps you’re a member of my WhatsApp group?

I’d love to see a comment on my blog, Diary of a Muzungu, or perhaps on one of the podcast directories. Let me know what you like, let me know what you don’t like, and see you next week!

Thanks for listening.

Welcome to my world!

Tune in every week to The East Africa Travel Podcast for the dawn chorus, travel advice, chats with award-winning conservationists, safari guides, birders, lodge owners, and wacky guidebook writers.

- Sign up to my newsletter to receive an alert for new episodes.

- Subscribe to the East Africa Travel Podcast on Apple, Spotify and all the popular podcast directories.

- Follow Charlotte Beauvoisin, Diary of a Muzungu on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

- If you have any questions or comments, I’d love to hear from you.

- Send an email or a Whatsapp voice note.

Stay tuned for more sounds from the jungle!