In episode 6, join me – Charlotte Beauvoisin, author of Diary of a Muzungu – as I chat chimpanzees with Harvard University Professor – and close friend of Sunbird Hill – Dr. Richard Wrangham whose work combines primatology, evolutionary biology and anthropology. Listen in to hear:

- What do sex, violence and cooking have in common?

- How do bees protect villagers’ gardens from hungry elephants?

- How long did Richard work in Gombe with Jane Goodall?

- Why shouldn’t people have chimps as pets?

- What is the Kibale Chimpanzee Project?

- How does attending the Kasiizi Project’s secondary school protect the forest?

- Dr. Richard Wrangham has been visiting – and lived in – Uganda for 40 years. Which National Parks does he recommend tourists visit?

- And lastly, why did Richard suggest Julia Lloyd eat a hairy caterpillar?

Welcome to my world!

Tune in every week to The East Africa Travel Podcast for the dawn chorus, travel advice, chats with award-winning conservationists, safari guides, birders, lodge owners, and wacky guidebook writers.

- Sign up to my newsletter to receive an alert for new episodes.

- Subscribe to the East Africa Travel Podcast on Apple, Spotify and all the popular podcast directories.

- Follow Charlotte Beauvoisin, Diary of a Muzungu on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

- If you have any questions or comments, I’d love to hear from you.

- Send an email or a Whatsapp voice note.

Stay tuned for more sounds from the jungle!

Episode 6. Chatting chimpanzees. In conversation with Dr Richard Wrangham FINAL

[00:00:09] Charlotte: Welcome to Episode 6 of the East Africa Travel Podcast, hosted by me, Charlotte Beauvoisin, author of Diary of a Muzungu, and blogger in residence at Sunbird Hill on the edge of Kibale Forest in Western Uganda.

[00:00:25] Thanks for tuning in.

[00:00:27] One of the reasons I wanted to create this podcast is to introduce you to some of the extraordinary people that I’ve met during my last 15 years living here in Uganda and traveling around East Africa.

[00:00:40] In today’s episode, I talk to an occasional neighbour and fellow Brit whose been living in Uganda and visiting Uganda for 40 years.

[00:00:51] Sex, violence and cooking. Well, you probably didn’t expect me to cover these kinds of topics on a podcast about travel and conservation. So who might our next guest be?

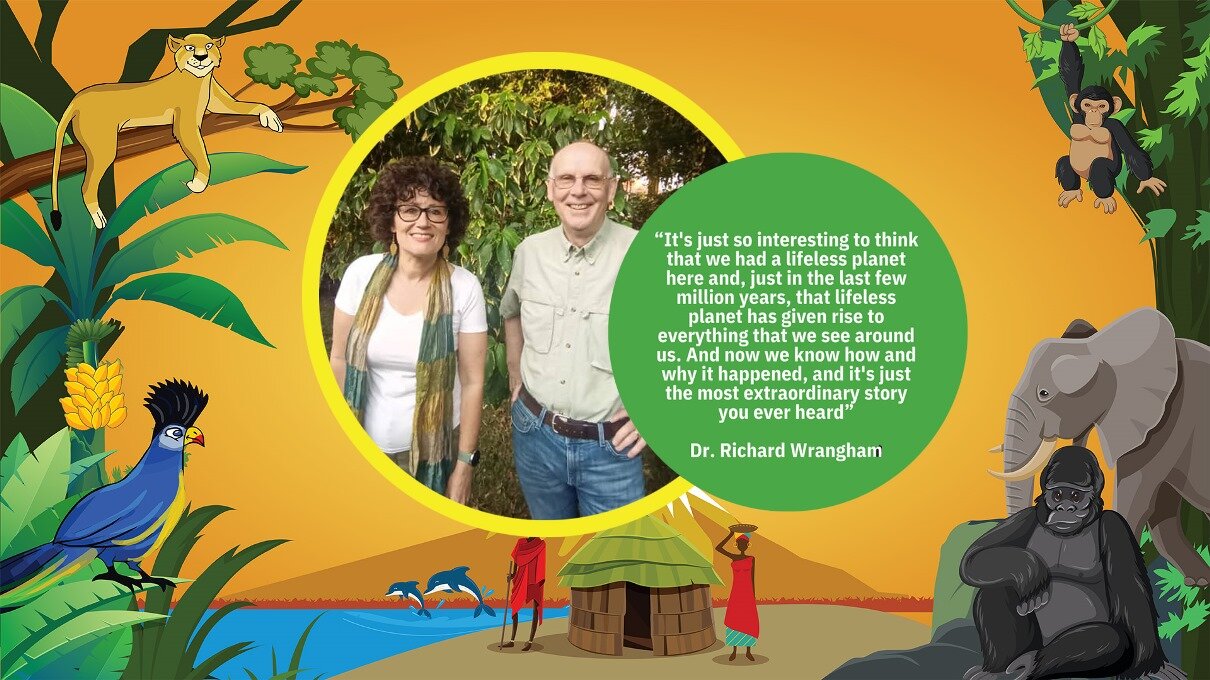

The work of Briton Dr Richard Wrangham combines primatology, evolutionary biology and anthropology. He started working in the 1980s with the Kibale Chimpanzee Project. However, Richard Wrangham is best known for his work on the evolution of human warfare, described in his book, Demonic Males. In his book, Catching Fire, How cooking made us human, Wrangham argues that cooking food played a crucial role in human development.

[00:01:35] Richard is a Harvard University professor, retired, and patron of the Great Apes Survival Partnership, also known as GRASP.

[00:01:44] We talk about working with Jane Goodall. How bees protect villagers from elephants. Shocking discoveries about chimpanzees. Why people shouldn’t have chimpanzees as pets. And what President Museveni said about primates. He also has a few recommendations of places where to travel in Uganda.

[00:02:07] When I daydreamed about the idea of launching a podcast, I scribbled a long list of interesting people that I’ve met over the years and Richard Wrangham was high on that list. He was my friend Julia’s mentor.

[00:02:23] When Richard and his wife Elizabeth and their young family lived in Kanyanchu, Julia was telling me how he loved trying all the different foods that a chimp might eat. It actually led to Julia eating a hairy caterpillar one day! I don’t think she was ever going to do that again, but she said she drew the line at black and white colobus monkey meat.

[00:02:46] Richard is a big part of our journey to where we are today. He mentored Julia who’s gone on to launch the NGO In The Shadow Of Chimpanzees here at Sunbird Hill, where I live. He is a mentor, inspiration and personal friend of Sunbird Hill. I so enjoyed talking to Richard and as I prepared to talk to him and also as I prepared to launch this episode for you, I started reading more about him and watching YouTube videos. One of them has over a million views. That’s how big a deal he is, particularly in the world of anthropology, internationally.

[00:03:26] Charlotte: Dr. Richard Wrangham, I want to start with how you came to be in Uganda the first time. What drew you here? Was it work? Was it chimps?

[00:03:36] Dr Richard Wrangham: Yes, it was chimps. In 1980, I was looking for a place to study chimps. And I wanted to make it somewhere where I could be long term. Because I had spent three years, in Gombe, working first of all as an assistant to Jane Goodall, and then as a student of her and her senior professor, Robert Hinde. That was an incredibly exciting time because that was a period of really making core discoveries about the nature of chimpanzee society. Jane and her team really discovered what chimpanzees were. one of our two closest relatives, how they lived. The real surprises were that even though we knew that chimpanzees were potentially fascinating in relationship to humans, it was still a sort of shock to discover that in many ways they exhibited behaviors that were reminiscent of the kinds of things that early humans might have shown.

[00:04:39] And so not just hunting other mammals, but then sharing the meat. Not just using tools, but making tools. Showing political sense that involved all sorts of complexities that echoed. familiar themes in, in humans. And then most dramatically, just as I was finishing my fieldwork there, the discovery that chimpanzees could go out and deliberately kill members of neighbouring groups in a way that was startlingly similar to the patterns that are shown in raids and ambushes among small groups of humans.

[00:05:17] So all of this was making chimpanzees just a fascinating species, and it meant that we wanted to do more than just rely on one or two sites to be able to understand how much variation there was across populations? Was this characteristic of a species as a whole? Or were there some of these cultural patterns?

[00:05:37] Or were they patterns of behavior that would only show up in certain environments? So there was a tremendous obvious potential for going to different places to study different kinds of chimpanzees. And with that in mind, I started asking about all sorts of contexts where they might recommend studying chimps.

[00:05:57] Tom Struhsaker was a primatologist who had been working with Gilbert Isabirye-Basuta, and Basuta had been studying the chimpanzees of Kibale from 1983 to 1985, and for various reasons, it seemed like a terrific place to go and start work. And frankly, there was one reason that has nothing to do with the science, but just to do with the fact that I wanted to be somewhere where I would feel comfortable long term, and that was that we had a couple of small children, my wife and I. And so we wanted to be able to go somewhere where we felt reasonably safe about the children, and Kibale, in the Kanyawara area that I was destined to work, is about 5,000 feet above sea level (1,700 meters or whatever it is). And that meant that the risks of malaria and some of the other diseases were a little bit lower. And we thought, well, this is great! Because then we can be there for many months or years at a time with our children.

[00:07:03] Charlotte: As somebody who lives very close to where your study site is, I live at Sunbird Hill, on the edge of Kibale National Park, we hear that chimps and human children shouldn’t mix, that chimps can be very dangerous, and you even hear circumstances where human babies have been kidnapped. Is that true? Because in Uganda, people really fear chimps, don’t they?

[00:07:27] Dr Richard Wrangham: Yeah, and quite rightly. Because chimps are dangerous, and because you know, you sometimes have this terrible situation where people have taken chimpanzees as pets and take them into their household and even then they forget that they are wild species, they are wild animals, and they can do terrible damage to humans; just in the same way they like to kill monkeys, they like to kill pigs; they like to kill small antelope, and eat them, so chimps are indeed potentially very dangerous. What we’re trying to do, naturally, is not only research, but conserve the chimps and help protect them. They’ve already shrunk hugely in number over the last century, and there are some people who feel that they’re not going to last for more than another century because of the expanding agricultural base that is in the forest.

[00:08:18] Charlotte: People are incredibly drawn to chimpanzees and I’ve watched them many times just sitting and eating figs and scratching and sleeping and they’re so like us, it’s unbelievable, isn’t it?

[00:08:30] Dr Richard Wrangham: And it does go in both directions, you know, the lovely, friendly, calm, relaxed interactions like us. And as you say, the tense ones that can lead to really difficult, unpleasant situations.

[00:08:42] Charlotte: This touches on a topic that I wanted to ask you about, which is over habituation. As you know, we have a mutual friend in Julia Lloyd, who was one of the team who habituate the chimpanzees that tourists now trek in Kibale and she said to me a few times that she’s worried the chimps are over habituated that they’re so used to humans that they don’t see them as a different species and are therefore more likely to attack them. Do you think that’s true? Is that a concern?

[00:09:08] Dr Richard Wrangham: I wouldn’t put it quite that way. I wouldn’t put it the idea that they don’t recognize we’re a different species because however much they are habituated to us, they know who they want to mate, who they want to fight with, who are their rivals, who are their friends, who are their enemies. It’s just that they get so comfortable being in the presence of humans that if something goes wrong, then they would feel relatively comfortable taking it out on a human.

[00:09:38] Charlotte: So they might lash out. You very occasionally hear of a chimp thumping or, you know, throwing its arm out at someone.

[00:09:46] Dr Richard Wrangham: Yes, right. And maybe it would be because they’re startled, or it could be a deliberate attempt to intimidate somebody that they just take a dislike to. And so I think the dangers of habituation are the fact that when people are very close to chimps, they can get very little warning about the possibility that this very strong species might attack.

[00:10:10] But, you know, it’s funny this line of questioning because, mostly when I think about chimps, of days when they are incredibly relaxed and very soft hearted and very comfortable with each other and very comfortable with researchers hanging around. You know, the sort of classic day of sharp sunlight coming down into the forest and there a mother lying on her back with a baby bouncing on her tummy and she just patting the back of the baby. And then another one totters over, and the two of them start interacting, and, and so on. I mean, these are the calm, again, human like, delightful interactions that really characterize them.

[00:10:51] Charlotte: How can tourists help, do you think, protect chimps?

[00:10:55] Dr Richard Wrangham: Well, by coming and seeing chimps, and by contributing their foreign dollars to the Uganda Wildlife Authority and the country as a whole.

[00:11:04] You know, in 2006, President Museveni stood up in front of a thousand delegates of the International Primatological Society in Entebbe and he said, “I like primates. I like primates because, other than remittances sent by Ugandans living abroad, the biggest source of foreign exchange is tourism and” he said “more than half of that comes from tourism to see primates.”

[00:11:30] Well, of course, he was thinking mostly about gorillas. The fact is that Uganda is the only country where you can have a really strong expectation of seeing both chimpanzees and gorillas. Well that’s an amazing thing to do!

[00:11:43] Charlotte: I don’t know if you’ve heard the term the big seven, we say Tanzania and Kenya may have the big five but we’ve got the big seven.

[00:11:51] Dr Richard Wrangham: Oh I haven’t heard of that, that’s great! Yes a lot of people as you know come for the gorillas and the chimps but then they stay for everything else. So it’s great when tourists come. And by the way, you know, when you say what can they do, I think one of the things they can do, really, is learn about the apes, and learn about responsible tourism.

[00:12:09] You know, learn that it is really important not to throw plastic bottles out of your window as you drive along.

[00:12:16] Charlotte: And how about feeding wildlife? We were talking about that yesterday. We work in conservation and I support various conservation projects. We’re so close to the subject matter we can easily make assumptions, can’t we, about people’s levels of awareness. So where have we gone wrong that somebody’s visiting a national park and they don’t know that they shouldn’t feed animals and they might slip a bit of rubbish out of the window and that kind of thing. How do we fix that?

[00:12:43] Dr Richard Wrangham: Well, I don’t know exactly, but I do have great admiration for the arrangements at Bwindi, where, in order to go and see mountain gorillas, you spend the night in Bwindi, and then what happens the next morning, the first thing that happens is, you go to a visitor centre, and you’re given a lecture. And it’s not done in a difficult, disciplinarian way or anything. There’s women dancing, and there’s a festive atmosphere, and everyone’s excited because they’re getting to go see gorillas. But nevertheless, you have a 20 minute lecture, which really lays it out in a very, very good way. I wish we could do that every day, in some form or another, whenever anybody enters the National Park. I mean, it’s not practical for going through Queen Elizabeth, but, you know, you could do something like that in, in Kanyanchu, in other places where you see chimpanzees.

[00:13:26] Charlotte: You mentioned Jane Goodall. I know you’re friends. Did you work with her back in Gombe?

[00:13:31] Dr Richard Wrangham: Actually, I finished my undergraduate. time at Oxford in 1970 and I wasn’t sure what to do, but meanwhile I wrote to Jane, met her in 1970 and I was just very lucky because it was a time when she wanted to have research assistants and so I spent three years in Gombe and it was a very exciting time because there were something like eight students there and we were learning how to follow chimps.

[00:13:59] I think I was the first person to base my PhD on following from dawn till dusk, you know, all day observations. That was particularly thrilling because it gave a real sense of the life of a chimp, which can sometimes do days far out of time.

[00:14:15] Charlotte: The other person that’s a very famous primatologist is Dian Fossey, and you’ve worked with her as well, is that right?

[00:14:22] Dr Richard Wrangham: Well, I didn’t really work with her at all, but I spent a week or ten days with her in 1976/77, just around that new year. We did our PhDs in neighbouring offices in Cambridge, in England, and so we became friends.

[00:14:37] Charlotte: I see a lot more humanity in conservation now. I think we are very much aware that we can’t have wildlife conservation without really investing in people and looking for livelihood. But it’s a tough road, isn’t it? As somebody who lives on the edge of a national park, there aren’t many job opportunities there, and you really have to have a long term view.

[00:14:57] Dr Richard Wrangham: That’s absolutely right, and Uganda has still one of the highest population growth rates in the world. And the population growth rate around Kibale and some of the other parts is particularly high.

[00:15:09] The challenges are considerable. And that’s why my wife, Elizabeth Ross, 26 years ago, I started a project, the Kasisi project, designed to really try and increase the opportunities available for children. That’s a long term project which involves 16 schools and almost 10,000 children and what we’re trying to do is to make sure that as many as possible get to go to secondary school and giving them a really strong sense of wildlife education about the value of the forest and inhabitants.

[00:15:44] Charlotte: The school looks really lovely. I also see you’ve got a project that involves beekeeping and some kind of elephant deterrent. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

[00:15:54] Dr Richard Wrangham: Well, the elephant deterrent is a very practical issue. What the Uganda Wildlife Authority has done is to put a trench around the parts of the park where elephants are liable to come in and raid people’s agricultural areas, you know, their gardens, their fields. The problem is that when there are swamps, you can’t build a trench, and so the elephants quickly learn that that’s the way to get out of the forest and into people’s gardens. So the solution that we’ve been trying is to string up beehives on wires that go all the way across the swamp. The idea is that the elephants come along and they knock the wire and the bees wake up, as it were, and they fly out and they attack the elephants. Elephants are very afraid of bees, partly because one of the awful things that can happen is the bees can fly up the elephant’s trunk and sting them up there. And, you know, it’s very, very uncomfortable for them.

[00:16:50] Charlotte: It sounds like a cartoon! But it does really happen.

And so if somebody wanted to go chimp tracking in Kibale forest in Uganda, could they go and visit the school or the beehives?

[00:17:01] Dr Richard Wrangham: Well, yes, I mean, there’s a guesthouse on the school grounds, which is designed to allow people to both experience the school and have a base, a very cheap base compared to some of the luxury hotels, to go chimp tracking.

[00:17:13] Charlotte: Perfect. Talking of tourism, I know you’ve traveled extensively around the country. Which places would you recommend tourists visit?

[00:17:22] Dr Richard Wrangham: Well, I think that one of the most exciting is Kidepo. Kidepo is in the northeastern part of Uganda and is unlike the rest of Uganda, which is mostly, or much of it, relatively good for growing crops.

[00:17:34] Kidepo is in a much drier area, which traditionally used to have cattle in it, pastures, people like the Karimojong. And now, it has quite a large area which is open to all sorts of plains game. Not that many trees there. And you’ve got lions and cheetahs and leopards you have.

[00:17:54] Charlotte: You have large herds of buffalo.

[00:17:55] Dr Richard Wrangham: And you can really stretch your eyes there. And then if you come further west to Murchison Falls National Park, you’ll see a slightly different pattern of the savannah, representing in some ways just a little bit of extra rain, and the dramatic Nile plunging over the Falls with lots of elephant and many other animals, including giraffes.

[00:18:16] And these are places that are big enough that you can go in them and kind of catch the sense of what it would have been like to be someone living out in the bush all those years ago, two million years ago, say, when humans were just beginning as a species. You can catch the Pleistocene breezes there.

[00:18:37] Charlotte: That’s a lovely thought.

[00:18:38] Dr Richard Wrangham: A romantic time.

[00:18:39] Charlotte: There’s so many things that we’ve touched on that we now take for granted. We know that chimps use tools, whereas a few decades ago, 50 years ago, we didn’t. But do you find that people are ever shocked by the fact that you relate humans and chimps so closely to each other in the same sentence? A lot of people are used to it, but there must still be some people who find it quite shocking.

[00:19:04] Dr Richard Wrangham: Yes, I mean, there are some people who have their faith in some kind of religious principles which completely challenges the notion that humans and chimps are significantly related to each other. It’s a very hard argument to sustain nowadays because of DNA.

[00:19:24] You know, you can say, until DNA came along, “Oh, well, I bet that underneath we really are different.” But then it turns out that if you take any cell in the body, you can just go down all those DNA nucleotides. It turns out that almost everyone is identical to a chimpanzee! But I think anybody who really wants to talk about it in a serious way has to come to grips with the fact that during the last 20 to 30 years, we have just completely overwhelming evidence of the story of human evolution because of the way genetics is added to everything else which is so much more interesting and so much more exciting a story than one that was dreamt up by our ignorant forefathers, wo thousand, three thousand, four thousand years ago. Now we have a story we can test and it just becomes more and more refined all the time.

[00:20:16] But it’s just so interesting to think that we have a lifeless planet here. And just over the last, few million years, that the lifeless planet has given rise to everything that we see around us. And now we know how and why it happened. And it’s just the most extraordinary story you ever heard.

[00:20:34] Charlotte: It really is.

[00:20:35] And thank you very much, Dr. Richard Wrangham. I could keep you talking for hours and hours. Thank you for being part of our podcast.

Dr Richard Wrangham: Thank you, Charlotte, for the wonderful questions.

[00:20:44] Charlotte: I just wanted to say how happy I am to be at this point where I can unlock these interesting conversations with all these intriguing people. I have a very long list of super interesting people from around the world. And what they all have in common is they are African or they live in Africa or they study Africa or they travel here or they study here. And that’s what we have in common: we have a passion for Africa and particularly for the natural world.

[00:21:18] You’ve been listening to the East Africa travel podcast with me, Charlotte Beauvoisin, author of Diary of a Muzungu. Thanks for listening.

It’s quite moving to finally be broadcasting live and inviting you into my little world. So please do get in touch and tell me what you think.

I really did only touch the tip of the iceberg in terms of the wide range of topics that I could have talked to Richard Wrangham about. But if you like our conversation, I’m sure that we can invite him back on the podcast in the future. In the meantime, please check out the show notes and my blog. There are lots of interesting links.

Read about the Kasisi Project, Sunbird Hill, chimpanzees, and travel to Uganda, and if you have any questions at all, please get in touch.

[00:22:12] Stay tuned for more sounds from the jungle.

[00:22:15] Now hit subscribe.

Welcome to my world!

Tune in every week to The East Africa Travel Podcast for the dawn chorus, travel advice, chats with award-winning conservationists, safari guides, birders, lodge owners, and wacky guidebook writers.

- Sign up to my newsletter to receive an alert for new episodes.

- Subscribe to the East Africa Travel Podcast on Apple, Spotify and all the popular podcast directories.

- Follow Charlotte Beauvoisin, Diary of a Muzungu on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

- If you have any questions or comments, I’d love to hear from you.

- Send an email or a Whatsapp voice note.

Stay tuned for more sounds from the jungle!

“It is an absolute pleasure to listen to your podcast, dear Charlotte. I can’t wait for more conversations and stories with the sounds of the animals and the forest in Sunbird Hill! I love this relaxed atmosphere where there is time to talk and listen, to give tips, and to think without hurry. It brings me back to Uganda in a glance! In these times when young vloggers tend to focus in a speedy way on practical tips (basically where to eat, sleep, and take selfies for social media), your podcast is a gift for people who appreciate a deeper look into cultures and wildlife with knowledgeable voices. Amazing, congratulations!”

Thank you so much for listening – and for your wonderful response!

I’ve always been more of ‘an immersion traveler’ than a bucket list type and spending lockdown here on the edge of Kibale Forest only reinforced that. It’s amazing how rarely I get bored here. For example today: I spotted the biggest, hairiest, fluffiest caterpillar I have ever seen. At 70mm long – I always keep the ruler nearby 😉 – that has to be one mega moth one day!